Nutrition plays a pivotal role in achieving fitness goals, and understanding how to read a nutrition facts panel is a crucial skill for anyone on a fitness journey. As a personal trainer, empowering your clients with the knowledge to interpret these labels can contribute significantly to their overall well-being. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore the history of the nutrition facts panel, or nutrition label, its key elements, and provide insights on how to teach clients to make informed choices.

The Historical Perspective on the Nutrition Label

To provide a quick reference to the evolution of this movement, the timeline below briefly notes the major acts and/or events that ultimately led to these changes.

- 1980 – the FDA becomes involved with an initiative to improve the content and format of food labels. First dietary guidelines published.

- 1990 – Nutrition labeling becomes a requirement via the Nutrition Labeling & Education Act (NLEA).

- 2002 – Nutrition Label Reform and public commenting begins.

- 2014 – FDA proposed two rules on which it requested public comment for the changes to the NFP (Nutrition Facts Panel) and RACC (Reference Amount Customarily Consumed – we know these as “serving sizes”).

- 2015 – FDA holds a comment period for supplemental rules, which included a percent daily value (%DV) for added sugar.

- 2016 – FDA published its final rules which mandated a new nutrition label to be unveiled by July 26, 2018.

- 2018 — FDA Rolls out new nutrition label

- 2020 — Manufacturers with $10 million or more in annual sales were required to update their labels by January 1.

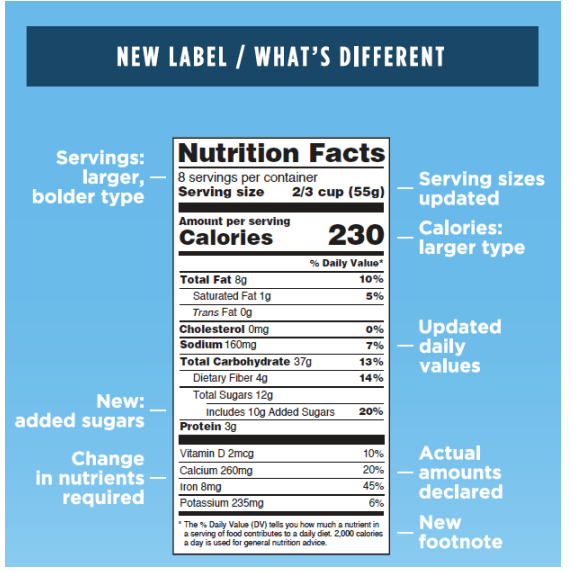

General Overview of 2018 Changes

As personal trainers and wellness leaders in the industry, we need to become educated about the following changes so that we may assist our clients in becoming wise consumers in the food industry.

These recent changes primarily include:

- The more relevant Serving Size is bolded to be more visible versus servings per container.

- The visibility of Total Calories is increased by the use of larger and bolded font. Even better than having the total calories listed per serving, the new labels will reflect total calories per package/container for products that contain MORE than a single serving. This allows individuals to quickly evaluate caloric cost if they consume more than a single serving.

- Calories from Fat will no longer be listed. Researchers found this item to be confusing for consumers as it didn’t really provide usable or relatable information for the general public.

- Multiple changes to %DVs.

- Added Sugars declaration as well as and a %DV for added sugars

- Changes to mandatory declaration of vitamins and minerals

- Declaration of absolute amounts of vitamins and minerals will be provided.

Breaking Down the Nutrition Facts Panel

Even though 67% of consumers read and examine nutrition labels (Salge, 2016), they often misinterpret the information when making purchasing decisions. How consumers apply nutrition label information to their decisions is a stumbling block. Luckily, personal trainers and health coaches can help teach clients how to use a nutrition facts panel effectively and consistently.

The Name Game

Most of the terms used in food labeling are straightforward. Their signficance, however, sometimes exaggerated or downplayed by advertising claims and the spin game they often play, can be a source of confusion.

- Serving size: The amount of food the information refers to. Servings per container: The number of servings in the entire product or package.

- Percent daily values: Shows how a food fits into an overall daily diet based on a daily intake of 2,000 calories.

- Calories: The total number of calories in one serving of this food.

- Calories from fat: The total number of calories from fat in one serving of this food.

- Total fat: The weight of fat (in grams) in one serving of this food.

- Saturated fat: The weight of saturated fat (in grams) in one serving of this food.

- Sodium: The weight of sodium (in milligrams) in one serving of this food.

- Protein: The weight of protein (in grams) in one serving of this food.

- Total carbohydrates: The weight of both complex and simple carbohydrates (in grams) in one serving of this food.

- Sugars: The weight of simple carbohydrates (in grams) in one serving of this food; to determine how many complex carbohydrates are in the food, subtract the sugars listed from the total carbohydrates.

With a clear understanding of the key label words behind you, there are several other important values to consider before concluding that a food product in question is a healthy, low-fat food.

Check the List

Food ingredients are listed in descending order according to their quantity in that food. The first three or four ingredients listed usually comprise most of the product.

Bear in mind, however, that fat and sugar come in many different forms, so that even if they are not one of the first three ingredients, the food can still be very high in fat and/or sugar.

Shortening and Sweetening

Other “names” for fat include hydrogenated vegetable shortening, butter, margarine, oil (coconut, safflower, palm, etc.), lecithin, lard, and cream solids.

Other names of sugars include fructose, honey, corn sweeteners, molasses, maltose, corn syrup, fructose, galactose, glucose, and dextrose.

If only one of these names appears among the first few ingredients on the label, or if several of them are listed throughout the label, this food is likely to be high in fat or sugar.

Scrutinize Total Fat and Saturated Fat

When checking the label of a food, always check the line that reads “total fat.” Most experts believe you should get no more than 25 percent of total daily calories from fat. For someone who weighs 160 pounds, that would be about 72 grams a day.

Before purchasing any food, check the total fat to see if that product fits into your eating plan. Just below the “total fat” line is “saturated fat.” Again, you want this number to be very low, since this type of fat is linked to obesity and heart disease. No more than 10 percent of calories should come from saturated fats. For the average person, this amounts to between 7-10 grams a day.

Determine the Percentage of Calories from Fat

In addition to listing the ingredients, nutrition labels provide the information necessary to determine the percentage of calories from fat in a specific food product. Knowing this is far more important than simply knowing the number of grams of fat in the food product: Just as you want less than 25 percent of your total daily calories to be from fat, you also want to try to eat foods that get less than 25 percent of their total calories from fat. Just because a food product has a low number of fat grams, it is not necessarily a low-fat, healthy food.

When checking nutrition labels, be sure determine the percentage of fat calories in addition to the number of fat grams. To determine the percentage of calories from fat of a food product, look for two important numbers: calories per serving and total grams of fat per serving.

Since you want to know what percentage of the total calories are fat calories, you must first convert the grams of fat into calories. Remember, there are 9 calories per gram of fat. To calculate the fat percentage of the food: Multiply the number of grams of fat by the number 9 (9 calories per gram of fat). Then, divide this product by the total calories per serving. The result is the percentage of fat calories.

Putting the Entire Nutrition Facts Label in Perspective

By integrating nutrition label reading into your training sessions, you not only enhance their nutritional knowledge but also foster a sustainable and healthier lifestyle. Together, you and your clients can navigate the complexities of nutrition labels and pave the way for lasting success in their fitness journey. When breaking down the elements of the label with a personal training client, the following list will walk them through the significance of each element in order:

- Serving Size Awareness

- Emphasize the importance of serving size awareness. Clients should understand that the information on the panel is based on a specific serving size, and consuming more or less will impact the nutritional intake accordingly.

- Total Calories

- Highlight the significance of total calories. The bolded and larger font for total calories is intentional—it’s the first thing clients should notice. Explain that this figure represents the energy content in one serving and, if applicable, per package or container.

- Macronutrients

- Fats:

- Discuss the total fat content and the removal of “Calories from Fat.” Clarify that while fats are essential, clients should focus on the type of fat (saturated, unsaturated) and aim for a balanced intake.

- Carbohydrates

- Break down the carbohydrates section, particularly the distinction between total carbs and dietary fiber. Encourage the consumption of fiber-rich foods, as it contributes to satiety and digestive health.

- Proteins

- Mention that protein remains unchanged and is a vital macronutrient for muscle repair and growth. Emphasize the role of proteins in supporting fitness goals.

- Fats:

- Micronutrients

- Vitamins and Minerals

- Explain the mandatory declaration of certain vitamins and minerals. Provide examples of why Vitamin D and Potassium are essential and how clients can use this information to ensure a balanced diet.

- Vitamins and Minerals

- Added Sugars

- Address the new focus on “Added Sugars.” Teach clients to differentiate between naturally occurring sugars and those added during processing. Emphasize the importance of limiting added sugar intake for overall health.

- Percent Daily Value (%DV)

- Clarify the purpose of %DV. This indicates how much a nutrient in a serving contributes to a daily diet based on a standard 2,000-calorie daily intake. Help clients understand that %DV can guide them in making healthier choices.

Practical Tips for Teaching

- Interactive Nutrition Label Reading

- Conduct label-reading sessions with clients during sessions. Bring in actual food items, and together, analyze the nutrition facts panel. This hands-on approach enhances comprehension.

- Real-life Application

- Relate label reading to everyday scenarios. Discuss how a client’s favorite snacks or meals align with their fitness goals and how making small adjustments can lead to significant improvements.

- Meal Planning

- Integrate nutrition label reading into meal planning sessions. Teach clients to plan meals that balance macronutrients and meet their nutritional needs. Offer guidance on choosing nutrient-dense foods.

- Visual Aids

- Use visual aids such as charts and diagrams to simplify complex concepts. Create a visual representation of a balanced plate, showcasing the proportions of macronutrients and how they align with the nutrition facts panel.

- Label Reading Apps

- Recommend user-friendly apps that can scan barcodes and provide instant nutritional information. This allows clients to practice nutrition label reading in real-time and make informed choices while grocery shopping.

Nitty Gritty Nutrition Label Details

Carbohydrates

The biggest changes are seen in the carbohydrates section.

- Dietary Fiber: The Daily Value for fiber increased from 25g to 28g while the caloric value will be reduced from 4kal to 2 kcal/gram for non-digestible soluble fiber. Since fiber is considered a “nutrient of concern” (one that Americans do not consume enough of), this increase challenges consumers to eat an adequate amount.

- Sugars now referred to as “Total Sugars” and the label will include a declaration of “Added Sugars” or those sugars added during the processing or packaging of the food.

- The FDA established a Daily value 50g for added sugars.(<10% of a 2,000-calorie diet) Currently, added sugars make up about 13% of the American diet (Salge, 2016). This declaration hopefully makes the consumption of these sugars a more conscious behavior rather than an “out of sight out of mind” aspect.

- The Daily Value for total carbohydrates decreased from 300g to 275g.

- The voluntary declaration of “Other Carbohydrates” was be removed.

Fats

Dietary Fat is the second of the macronutrients to see changes. The primary change included an increase in the Daily Value of “Total Fat” from 65g to 78g. This is in addition to the removal of the “Calories from Fat” notation. While carbohydrates and fats will see changes, protein will remain the same.

Micronutrients

The following are changes to the vitamins and minerals categories on the previous label:

- A mandatory declaration of Vitamin D and Potassium

- Quantitative amounts of Vitamin D, Calcium, Iron, and Potassium

- Voluntary declaration of Vitamins A and C (unless the nutrition label contains a claim).

Summary of Daily Value Changes

| Nutrient | Current DV | New DV |

| Fiber | 25g | 28g |

| Vitamin C | 60mg | 90mg |

| Vitamin D | 400IU | 20mcg (800 IU) |

| Potassium | 3,500mg | 4,700mg |

| Calcium | 1,000mg | 1,300mg |

| Sodium | 2,400mg | 2,300mg |

| Total Fat | 65g | 78g |

| Total Carbohydrate | 300g | 275g |

(Storey & Salge, 2016)

RAAC Changes (serving sizes)

- The serving sizes increased for many items including cereal, bagels, ice cream (did anyone else do a little cheer?), and soda.

- The serving size for yogurt decreased.

- There are 25 new RACC categories established including one for appetizers and dried soup mixes.

- All containers that contain more than 2 servings must include information for the entire container as well as for a single serving. This will appear as dual columns: “One Serving” and “Whole Container”.

What about “Organic”?

Increasing our awareness of what is in the food we eat can lead to better health and maybe even greater success at the gym. Even with advances in food labeling, weighing producers’ marketing claims against nutritional facts can still be a tricky business, however.

One type of label intended to separate fact from marketing hyperbole in the United States is the federal “organic” food certification program.

As it pertains to agricultural production, Webster’s dictionary defines the term “organic” as “of, relating to, yielding, or involving the use of food produced with the use of feed or fertilizer of plant or animal origin without employment of chemically formulated fertilizers, growth stimulants, antibiotics, or pesticides.”

According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), produce can be labeled organic if it has been certified to have grown on soil with no prohibited substances applied for three years prior to harvest. Prohibited substances in this case include most synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. When a grower must use a synthetic substance for a specific purpose, that substance must first be approved according to criteria that examine its effects on the health of potential human consumers as well as the health of the environment.

In the US, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sets the standards on levels of residue such as pesticides that it says are not harmful to humans. If a food dons a USDA Organic label, it simply means that it has been produced and processed according to the USDA standards. The levels of residues on most products–whether produced using organic methods or from nonorganic ones–are not allowed to exceed EPA-mandated safety limits.

In order to bear the “USDA Organic’ label, a product must be USDA-certified as having been grown organically. But why aren’t many, if not most, items at the local farmers’ market labeled “USDA Certified Organic”? One obvious explanation is that perhaps the food wasn’t grown in strict accordance with organic farming practices.

But another explanation might simply have to do with how much organic produce or meat the “organic” farmer or rancher in question sells annually. Producers who sell less than $5,000 a year in organic foods are exempt from the federal certification program. The USDA does permit such small producers who choose not to be certified to tell customers that they are using organic methods of production word-of-mouth style, however. So next time you’re at the farmers market, when in doubt, just ask.

Furthermore, products may have been grown according to USDA organic standards, yet the farmer (especially small farmers) did not go through the certification process to obtain this label. The process isn’t cheap and small farmers may opt to market their products to customers with a high level of trust.

Is “Natural” Organic?

Products that are completely organic–such as fruits, vegetables, nuts, eggs, and other single-ingredient foods–can be labeled 100 percent organic and can carry the USDA seal.

For processed, multi-ingredient foods, however, USDA organic standards are more complex. To bear the organic label, processed foods cannot contain artificial preservatives, colors, or flavors and their ingredients must be organic–with some exceptions. For example, processed organic foods may contain some approved non-agricultural ingredients, such as the enzymes used to produce yogurt, the pectin used in fruit preserves, or the baking soda commonly used in baked goods.

As for organic meat, federal regulations require that animals are raised in living conditions that accommodate their natural behaviors (such as the ability to graze on pasture for cows or forage the yard in the case of chickens), receive 100 percent organic feed and forage, and not are administered antibiotics or hormones.

The USDA does not regulate the label “natural” except when it is used in conjunction with meat and poultry products. To be labeled as “natural”, meats and poultry must have no artificial ingredients, no added color and minimal processing. Minimal processing means that the product was processed in a way that does not fundamentally alter it. Fortunately for consumers, the label must include a statement explaining the meaning of the term “natural”, such as “no artificial ingredients” or “minimally processed.”

Processed Food Labeling

Foods that have more than one ingredient, such as many cereals, can use the USDA organic seal plus the following wording, depending on the number of organic ingredients:

- “100 percent organic”. To use this phrase, products must be either completely organic or made of all organic ingredients.

- “Certified Organic”. Ninety-five percent of the ingredients are certified organic, excluding salt and water.

- “Organic”. Products must be at least 95 percent organic in order to use this term.

- “Made with organic ingredients” Products that contain at least 70 percent organic ingredients are allowed to say so on the label, but they are not allowed to use the seal.

- No Label Claims = Less than 70 percent of the ingredients are certified organic.

Is Organic “Better”?

Organic producers use natural substances and physical, mechanical, or biologically based ways of farming to the greatest extent they can. But is the food they produce more nutritious and does it harbor fewer residual chemicals than conventionally raised counterparts?

The current scientific literature points to a micronutrient benefit of consuming organic food products. One study reported higher antioxidant concentrations (particularly polyphenols) and lower levels of pesticides. Others found organic dairy products to have increased levels of omega-3 fatty acids, and even improved fatty acid profiles in organic meat products.

Still other studies have suggested that consuming organically grown or raised foods may reduce exposure to residues from pesticides and herbicides and those bacteria that have become resistant to the antibiotics used in conventional farming, which may be more than enough reason to select organic products for most.

Beyond analyzing the composition of the foods themselves is measuring health benefits of eating organically. A meta-analysis of 35 studies reported that organic food consumption “was associated with reduced incidence of infertility, birth defects, allergic sensitisation, otitis media, pre-eclampsia, metabolic syndrome, high BMI, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.”

Ironically, some food that is produced organically might not be labeled as such since producers must pay to use the USDA Certified Organic seal. A common criticism of the organic label program is that the added cost of the certification and the additional costs involved in organic production are often passed on to the consumer.

But for many people, choosing organic foods has as much to do with ethics as it does with health concerns or the grocery bill. Some consumers select organic foods over their conventionally grown counterparts because they prefer the taste alone, and many organic devotees are quick to point out that organic farming methods are aimed at helping the environment by conserving water and soil quality.

Better Shop Around

Many consumers in the United States are so numbed to advertising copy that we are scarcely conscious of it. When comparison shopping, always remember to read the ingredient list: Even if a product label states that it is organic or contains organic ingredients, that fact alone doesn’t necessarily make it a better choice in terms of the amounts of sugars, fats, or sodium it contains.

Taken together with nutrition facts, ingredient lists, and dietary claims printed on food packages, the “organic” label might just seem one more piece of information to sift through when going to the grocery or market. But making the effort to understand what “organic” really means can help a shopper make better-informed decisions, and there is much to be said for that.

References

www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/nop

usda-organic-label-means/#more-39051

www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/ams.fetchTemplateData.dotemplate=TemplateC&navID=NationalOrganicProgram&leftNav=Natio