It is imperative for recreation and professional golfers to train optimally to prevent injury and improve their game. Strength training, cardio, flexibility work, and of course, the all-important recovery all play a role in a golfer’s fitness. Here are the most important golf fitness components personal trainers need to know for players to get the most out of their training and improve their game on the course!

Understanding Golf Mechanics

Anyone guiding a program for a golfer would do well to understand the mechanics of a golf swing. Many recreational golfers are likely to get injured due to an inefficient swing with poor mechanices.Once a client has sustained an injury, he or she is even more susceptible to another injury. This makes it even more important for the client to be educated about his or her condition, how to strengthen correctly, and how to take a holistic training approach to return to the game.

Movement Analysis: Human Movement Training for Golf1

When we look at golf in terms of swing mechanics, it is important to understand functional anatomy and biomechanics to produce the necessary force to hit the ball.

The golf swing consists of three major phases:

- preparation

- execution phase(backswing and downswing)

- follow through.

Preparatory phase and setting1

The posture and alignment of the golfer influence the golfer’s ability to rotate properly, transfer weight, and maintain good balance during the swing. The body must be aligned so that feet, hips, and shoulders are parallel. The golfer’s left arm is straight while the right is partially flexed keeping the head positioned over the ball.

Muscles contracted: Rectus abdominis, deltoids and forearm flexors.

Backswing phase1

The purpose of the backswing is to establish a perfectly balanced powerful position at the top of the swing. Here, the hands and the shoulders must start in one motion. The weight of the feet in the stance is shifted laterally from the front to the rear foot. This shifting increases the range of hip rotation. At the top of the backswing, the shoulders are coiled, the hands are swung high and the arms are extended.

Muscles contracted: Latissimus dorsi, teres major, teres minor, and quadriceps. The extensors stabilize the golf club.

Downswing-follow-through phase1

The downswing is initiated by hip rotation. At this point, the golfer must lengthen the lever arm, which results in an increased acceleration of the club head. Simultaneously while the hip turns, a transfer of weight occurs. The weight is shifted from the back foot to the front foot. This shifting of weight enables the golfer to increase the impact area and improve accuracy.

When the downswing is initiated by the hips, and the turning of the hips unwinds the upper part of the torso, the shoulders and arms flow easily into the swing. At the point of impact, the wrists straighten while the trunk produces the force with other muscles producing a maximum striking effort.

Restoring your client’s drive: Strengthening the “weak link”

Many muscles support the lumbopelvic junction and contribute to its control and stability. Per the research, anatomically and biomechanically, the focus of core strengthening should be on strengthening the weaker erector spinae/multifidi, external obliques, TVA, and quadratus lumborum. There is biomechanical and motor control evidence that argues that different muscles and different control strategies may be involved in the control of different elements of stability.3

Training to Improve Spinal Stability and Prevent Low Back Injuries

Due to the muscular demands of the golf swing, training the trunk musculature improves performance and decrease injury risk. Proper spinal stability is the amount of trunk muscle co-contraction necessary to reinforce synergistic coordination between the nervous and musculoskeletal system.4

Strength Training

Strength training is more important than you may think for a golfer. Sure, a large part of golf is more about touch and nuance than it is about brute strength, but you may be surprised at how much your swing improves with a bit of strength training.

Golfers like Tiger Woods and Brooks Koepka have made a serious case for strength training (Koepka has one of the most powerful drives out there!).

Aside from building strength and muscle, one of the primary advantages of strength training is that it restores muscle balance; the golf swing is quite one-sided, which can cause muscle imbalances adversely affecting power, strength, and symmetry.

There’s also a saying: power comes from the ground up. While a golfer’s swing might seem like it’s all about the upper body, skipping leg day can reduce swing power drastically.

If you’re training a golfer, the following exercises will help them build the necessary strength for a solid, powerful swing. They cover push, pull, hinge, and squat movements.

- Squats/Bulgarian Split Squats

- Deadlifts including Romanian Deadlifts

- Hip Thrusts

- Military Press

- Dumbbell Bench Press (Flat & Incline)

- Carries (increase grip strength)

Once the golfer has built up a solid strength foundation, you can begin incorporating speed and power drills with explosive exercises like medicine ball throws, box jumps, and cable chops.

Warm-Up

Static stretching is a poor choice for movement prep since it will reduce power output in the muscle. This may only be appropriate when a muscle is known to be overactive (perhaps the calves?) A proper movement and muscle assessment will determine if this is necessary. Therefore, an ideal golf warm-up should be dynamic.

Which warm-up activities are deemed suitable enough before any stretching takes place?

Here is a list of warm-up ideas to get you started:

- Take a quick 5-minute walk upon arriving at the golf course

- Do a few light squats or lunges

- Have a few practice swings with your golf club a couple of times in slow motion

- If you have more time, resistance bands, and inclination, you can conduct a more intensive preparatory golf warm-up.

As you can see these are just a few simple ideas that you can easily get started with that will provide a quick warm-up, minimizing injuries before you start your round.

Now that we have got our muscles warmed up, let’s take a look at what types of stretching you can incorporate into your routine to help you stay healthy on the course. The following are a few dynamic stretches and mobility exercises that can help minimize the risk of golf injuries.

1 – Start With The Wrists

- Start by extending the arm out in front of you straight ahead with a closed fist.

- Flex the wrist so the knuckles of your closed fist are facing downwards and hold it there for a minimum of 10 seconds.

- Next, extend the wrist so that your knuckles are now facing upwards and again hold it there for a minimum of 10 seconds.

- Now, you will want to move your wrist up and down 10 times while keeping your arm out extended and your fist closed still.

- Finally, switch arms and do the same with your opposite wrist.

2 – The Forearm Stretch

- Start by extending out the right forearm.

- Next, take the right hand and begin pulling back on the fingers which will stretch them. By doing this, blood flow will now begin to circulate.

- Begin pushing the palm of the right hand forward away from the forearm, in essence, holding the same position in place without the help of the other hand.

- Hold this stretch for anywhere between 5-20 seconds.

- Switch arms and repeat the process.

3 – Arm Circles

This qualifies more as a warm-up, than a stretch!

- Begin by putting both arms out to the sides, both feet pointing forwards, whilst the shoulder blades are retracted.

- Rotate the arms in a circular movement while maintaining a golfer’s grip.

- Perform 10-15 reps with palms facing downwards whilst circling forward.

- Next, rotate the palms up and do another 10-15 reps circling arms backward.

Top Tip – Start off with 5-10 reps of small circular movements forward and backward. Then, do another 5-10 reps with larger circular movements forward and backward.

4 – Dynamic Shoulder Stretch

- Start with a golfer’s grip and place knuckles on the temples with thumbs pointing down.

- Begin touching the elbows together in front of the chest. This movement improves scapular mobility.

- Perform between 10-15 reps.

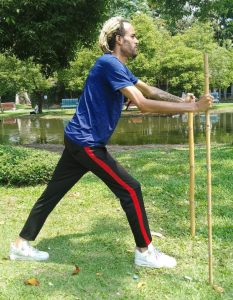

#5 – Hamstring Stretch

- Begin by taking two golf clubs and position both of clubs in front of the body facing downwards resting on the ground.

- Next, move the right foot forward and left foot back while keeping them in line with each other.

- Lean into the front leg by hinging at the hip socket whilst keeping your back straight. (Tension should be felt in the hamstring).

- Once the hamstring starts to feel taut, stop and lift up the toe of the front foot. This should increase tension in the back of the knee and thigh. Hold for 10-20 seconds.

- Stand up slowly, change legs, and repeat.

Top Tip – Make sure when lifting up the toe, your client is breathing in and out. Oxygen is essential for the muscles work; holding breath may increase the tension in the back of the legs.

During your warm-up make sure that you master your swing by consistently hitting irons, use this guide by The Left Rough so that you can do it right. Aerobic exercises are vital to blood circulation and cardiovascular conditioning, as well.

Core Work

A strong core is essential for a strong swing. Core work is often neglected during regular strength training programs, but dedicating time to it each week can significantly improve a golfer’s game.

Developing a strong core not only stabilizes the body during the swing, but it assists with the rotational movement that every shot incorporates.

Core work should be incorporated into a strength training program at least twice a week to get the full benefit.

Some excellent core stabilizing and strengthening exercises include:

- Dead bugs

- Pallof Press

- Side Plank

- Weighted Crunch

Cardio

Despite the ease of zooming around the course on a golf cart, golfers need a decent cardiovascular fitness level. This isn’t just to walk the course, which is a big part of playing the game, but also for stamina as they move through each round.

Incorporating cardio into a gym routine is essential. Three to four times a week is optimal, depending on the time available.

We suggest including a combination of HITT (High-Intensity Interval Training) and LISS (Low-Intensity Steady State) aerobic activity. This will help to strike a great balance between building endurance, burning fat, and improving fitness.

If possible, we also recommend varying the medium of training, cross-training between running, cycling, rowing, jumping rope, and using the elliptical.

It’s up to you and your client whether they split their cardio and strength training sessions or keep them together. Splitting is a little more effective, but it’s not convenient for some.

Mobility & Flexibility

While strength and endurance are important, mobility and flexibility are perhaps even more so. Without being able to move through a full range of motion smoothly and pain-free, golfers will never reach their full swing potential. Also, they won’t get the full benefit out of their strength training.

A huge part of flexibility is warming up before training. Dynamic stretching will get the muscles warm and flexible before they’re put through strength training exercises that will have them moving through a full range of motion.

If time allows, incorporating a flexibility and mobility day into the golfer’s training routines can be extremely beneficial. Due to the nature of the motion of a golf swing, flexibility is key. If a golfer is immobile or doesn’t have a full, smooth range of motion, the chance of injury is much higher.

Yoga is an excellent way to develop better flexibility. Just a day of yoga per week can help golfers stay mobile and flexible.

Recovery

As with any type of training, recovery is an essential component. But it’s often neglected and seen as wasted time. The truth is, the quality of recovery can have a huge impact on one’s physical health and fitness when they’re on the course.

Recovery is a day-by-day thing, and it varies slightly for everyone. But one of the most important things (especially for sportspeople) is rest. That means taking a day off from all exercise at least once a week, structuring exercise so that muscle groups aren’t overworked, and taking a full de-load week every 8 to 12 weeks.

Ultimately, your job is easier when your client is well-recovered as a trainer. Here are some areas you should discuss with your client to ensure that their recovery is an active part of their health and fitness and not a passive one.

- Electrolyte replacement

- Efficient hydration

- Compression treatment

- Foam rolling/massage

- Heat and cold treatment

- Consistent and ample sleep

- Rest days

- Deload weeks

Retraining inured areas for optimal performance

In order to retrain injured lumbar musculature, three things must be taught; motor control, core, and systematic strength training as described by Hibbs et al. Motor control is stability where the CNS modulates the efficient integration and recruitment of local and global muscles.

Core strength training is overload training of the global muscles which leads to hypertrophy as an adaptation to overload training. Systematic strength is overload strength training of the global muscles. Relearning motor patterns to properly recruit muscles in isolation is vital in order progress to functional positions and activities.5

In the next section, simple sport-specific exercises that you can teach the golfer client to target the “weak links” appear below.

Progression of golfing training

A following outline describes a 6-week return to the golf mesocyle.

Weeks 1 to 2: Relearning how to properly contact the transversus abdominis is vital.

Weeks 2 to 4: Static lumbar strengthening exercises beginning with planks and side planks are essential to rebuild the weak foundation of the lumbo-pelvic girdle. Progression can be made by increasing repetitions and/or altering the base of support(ie. four-point plank with alternating leg lift)

PRE’s: Since the Lat’s are one of the primary movers in all phases of the swing, lat pulldown exercises are an excellent exercise as well as seated mid-row exercise. While diagonal trunk chop simulates the golf swing. Stretching: The postural hip flexors, quadriceps, and lumbar extensors are vital for golf.

Weeks 4 to 6: Oblique and dynamic core stability strengthening should be included at this stage. Examples are standing medicine ball toss in the golfer’s stance, standing medicine ball toss throw(figure 8), seated on floor rapid trunk rotation using medicine ball in hands(twisted side to side) with knees bent.

Conclusion

Golf is a popular activity for the young and old providing an opportunity to play a game that enables someone to socialize while enjoying the outdoors. Golf requires practice, skill, finesse, and most of all patience. Understanding the fitness components you need to know for golf can help you to train a golfer to new performance heights.

However, it is important to understand a client’s full medical history and any injuries before designing and incorporating a regular strength training program. Core strengthening, flexibility training, and practice are all key elements to help your client to play optimally without injury.

While the fundamentals of strength training, cardio, flexibility, core work, and recovery are the same for everyone, golfers may struggle to understand how lifting weights can help their swing, or why doing core work will be a good thing for them.

Don’t forget to explain each one of these elements to your golfer client. Once they have a full understanding of the benefits of each of these components, it’s easy to see how their swing will improve, their balance will become better, injuries will be minimized, and ultimately, their golf game will get better.

About the Author

Biography: Chris Gellert, PT, MPT, CSCS, CPT is the President of Pinnacle Training & Consulting Systems. Gellert offers educational workshops on human movement, home study courses on human movement, and consulting services. As a clinician, author, presenter, with extensive experience having treated and worked with individuals’ of all ages with various spinal injuries, post surgical conditions, traumatic and sport specific injuries in industrial rehabilitation, outpatient and private practice settings. He is presently pursuing an advanced Master’s Degree in Orthopedics/Manual Therapy in Australia. For more information, contact www.pinnacle-tcs.com or email him at [email protected].

References

1. Carr, Gerry. 1997′ ‘Mechanics of Sport: A Practitioner’s Guide. Human Kinetics,’ pp. 136-137.

2. McHardy, A, MChiro, Henry Pollard, & Luo, K, 2007, ‘One-Year Follow-up Study on Golf Injuries in Australian Amateur Golfers,’ ‘ American Journal of Sports Medicine,Vol. 35, No. 8, pp. 1354.1359.

3. Hodges, P, 2003, ‘Core stability exercise in chronic low back pain.’ Orthopedic Clinical North American. Vol. 34, pp. 245-254.

4. Lehman, G, 2006, ‘Resistance training for performance and injury prevention in golf,’ Journal of Canadian Chiropractic Association. Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 27-42.

5. Hibbs, A et al, 2008, Optimizing Performance by Improving Core Stability and Core Strength,’ Journal of Sports Medicine, Vol. 38, No. 12, pp.995-1008.