Upper body dysfunction (UBD) may appear upon observation as simple shoulder dysfunction, as has been suggested with models such Upper Crossed Syndrome. But the glenohumeral (GH) joint does not function independently, nor is upper body function and movement limited to this one joint.

The Brookbush Institute has identified the signs of dysfunction associated with and created the following model of UBD. They have this to say about postural dysfunction:

“{It} effects length/tension relationships, resting tone, afferentation (sensory input), alters proprioception, joint dyskinesis, and maladaptive changes in connective tissue length.”

When dysfunction is present performance is hindered, so as fitness professionals armed with the right knowledge and approach, we can improve our clients’ performance and function by identifying the dysfunction and helping them to correct it. You should have already read about and performed and Overhead Squat Assessment and identified then corrected Lower Extremeity Dysfunction and Lumbo Pelvic Hip Complex Dysfunction before addressing UBD.

Developing a working knowledge of how key joint actions interact with each other is the first step in attempting to resolve UBD. And there is a LOT going on in the upper body. The ball and socket nature of the GH joint makes things challenging enough. The scapular motions can certainly complicate things further, so the more you expose yourself to the nuances of shoulder and scapular motion, the more easily you’ll grasp the complexities over time.

Signs of Upper Body Dysfunction

So what are we really looking for? Identifying the signs of UBD can be done with an Overhead Squat Assessment–a simple movement, though not easy to execute, in which compensations of synergistic dominance and muscle imbalance can be most easily identified.

When performing a squat while attempting to keep arms overhead, ideally, the arms will stay straight and alongside the ears as each squat is performed. If they cannot align with the torso and ears before even starting the squat, then that is a positive for “arms fall”.

If any of the following compensations are noted, then the client is positive for upper body dysfunction (UBD):

- Arms “fall” to the sides or forwards. (Best observed from side) If the arms drift outwards or the elbows bend (adduction) or fall forwards (flexion) this is an indication that the latissimus dorsi is short and overactive, and of short internal rotators and weak external rotators. Anterior delts might be short too.

- Scapulae Elevate–If the shoulders show marked elevation so that the neck is crowded, or visually assessing that scapulae are elevating, this is an indication of overactive downward rotators and anterior tippers of the scapulae. While it’s tempting to call this overactive shoulder elevation, there is more going on that meets the eye.

- *Anterior pelvic tilt–It might seem like excessive lordosis shouldn’t be related to UBD, however, many times a tight latissimus dorsi will contribute to anterior pelvic tilt, but usually it’s lumbopelvic hip dysfunction (LBD). If this sign is accompanied by “arms fall”, it could be both! (See? Complicated.) Do the modification below.

*To determine if lats are responsible for the anterior pelvic tilt during a squat, have your client repeat the squat with hands on hips instead of overhead. If the tilt remains, the lats are to blame. If the tilt disappears, it is indicative of LBPD.

- Spinal/Trunk flexion–This sign will only become apparent with hands-on-hips modification. If the spine rolls forward into flexion at the bottom of the squat, this means the deep intrinsic spinal stabilizers are weak, and the lats and obliques have been taking over. Putting the hands on the hips takes the influence of the lats away revealing the dominance of the obliques as they pull the trunk forward. But make no mistake, lats are overactive and short.

Which Muscles Need to Be Corrected?

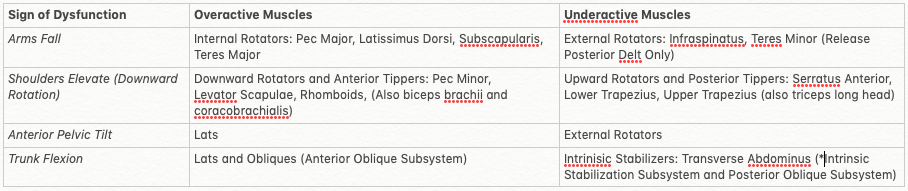

Well we’ve got a lot going on here so let’s refer to a chart to simplify:

It will help to get a strong handle on the above joint actions first and then you’ll be surprised how you’ll “see” the muscles, their attachments and joint actions as they should be, and recognize when they are not functioning optimally. If you are still uncertain of your client’s possible dysfunction after performing OHSA, performing specific shoulder mobility tests might help clear things up.

Bear in mind the posterior deltoid is an unusual muscle that tends to be lengthened yet overactivity, similar to the hamstrings in someone with an anterior pelvic tilt: The muscle is being pulled taut yet is being recruited in a lengthened position. This calls for myofascial release not stretching or strengthening.

The corrective approach will involve releasing the overactive muscles to calm them down and lengthen them with static and dynamic stretches. Simultaneously, you will attempt to activate and strengthen the long and underactive muscles so their actions can be integrated into functional movement.

The above is really an introduction to this model and I recommend further reading. You’ll see the bottom of the chart under trunk flexion makes reference to subsystems. These are more complex concepts but involve fascial and muscle connections that work together.

Note also, that dysfunction seems to start in one area, and like dominoes, start to impact other joint actions one by one. You might think of UBD as having “grades” that worsen as imbalances are left unchecked. Although every case is different and every body will vary, you might expect UBD to appear in the following worsening sequence:

- Latissimus dorsi and/or hyperkyphosis

- Overactivity and tightening of scapular downward rotators

- Rotator-Cuff Dysfunction (“Short” supraspinatus and subscapularis, “Long” infraspinatus and teres minor)

- Adaptive shortening of larger shoulder muscles (pectoralis major, deltoid, etc.)

- Cervical spine dysfunction (forward head syndrome)

Clients may always be a work in progress and despite your strongest efforts and commitment, you may not get them into perfect balance and alignment. But reminding them of the importance of this (to reduce injury and pain while also improving function, performance and efficiency) may also motivate them to become more aware of their posture and mind-muscle connections during daily life. Only through hypervigilance, then intrinsic awareness and consistent effort will long-lasting changes be made.

Reference:

https://brookbushinstitute.com/article/upper-body-dysfunction-ubd