“Core strength” has certainly been a fitness buzz phrase for years, and although the science has come a long way in the last few decades, so many fitness enthusiasts still don’t feel they’ve “worked” their core unless they dedicate a whole day to abs. It seems most folks are more concerned with the aesthetic outcomes of core work (you know, to reduce belly fat or boast a six-pack). I hear enough to know that an interest in true core strength and stability, with the main goal of overall strength and movement efficiency, has taken a bigger spotlight these days.

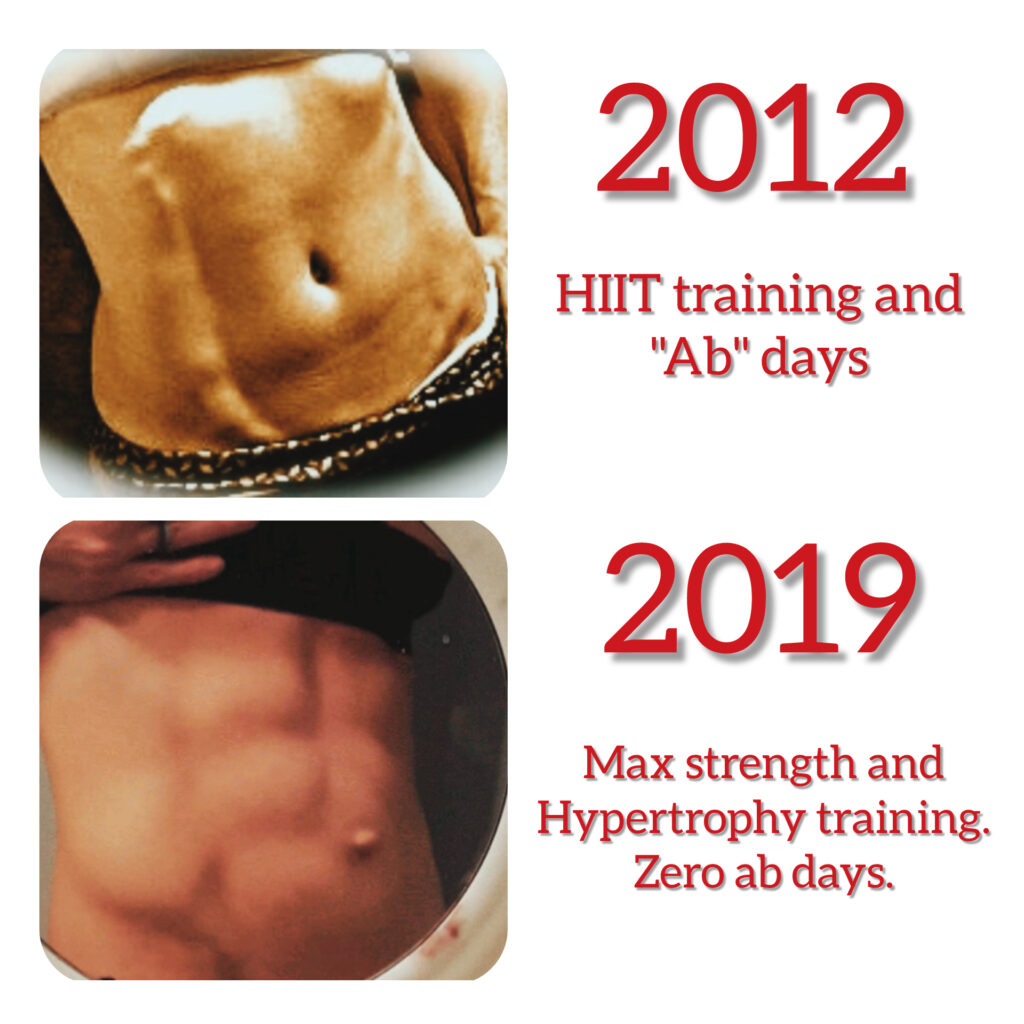

I’ll speak for myself when I say “ab day” for me has long since been extinguished from my routine, yet my abs have never been more ripped. (And that’s even after having kids). But more relevant is how I got there and what evidence there is that my muscles that support core strength are actually stronger than they were when I did 30-minute ab routines two or three times a week.

My Strength Routine Metamorphosis

This section is all personal story-telling, so feel free to scroll down to the research section if you want to skip the fluff. I just wanted to share my experiences over the years to put into context how I’ve settled on my current routine.

I got my start in bodybuilding when I was but a 12-year-old girl who was nicknamed, “chicken legs” by the boys on the school bus. I wasn’t all that skinny, but my structure was knobby and bony (it still is, but is hidden more by muscles). I discovered weight-lifting and weight-gainers, and I started my journey to become more muscular.

Up until my early 20’s, I studied Muscle & Fitness magazines and the like, adhering to hypertrophy-only programs. I did yoga as well but saw that as an entirely separate endeavor. It worked well enough for a while until I decided to pursue fitness as a career and learned so much more.

I aimed for a different goal: strength and conditioning. I learned to do pull-ups; because I hated leg day so much (my wacked-out hips and structure made it all very hard) I stuck with upper-body development and ab work since it was so much easier for me.

I taught an abs class twice a week. I produced a video (among others) called Ab-Shredder that gained a sizable following. I found every possible way to intensify bodyweight spinal flexion and rotation; the positive response by gym members and video fans was pretty universal. When doing 30 straight minutes of ab work with only brief rest, it’s most likely only endurance range training: 25-50 reps per movement.

Although I achieved visible development, it was not what one would expect from someone killing it on ab day.

What I was was not doing, however, was loading heavily on my lower body days, and I was certainly not loading my flexion movements.

Fast forward 10 years and HIIT became a “thing”. If it was hard, I was all in, and HIIT is unquestionably hard when done right. But that’s all I did. I dropped progressive hypertrophy training and embraced daily running, metabolic conditioning, tabata, and functional training.

I became a different kind of fit. And it worked for me at the time for the most part, but if I’m being honest, the cardiovascular challenge was always too unpleasant for me to really love my workouts. Also, my body did not look as developed as I wanted. (It’s okay, btw, to want your body to look a certain way; it’s not ok to detest it when it doesn’t cooperate)

When I became pregnant with my first five years ago, I took a step back from all of it. It wasn’t until my second turned one almost two years ago that I made a fitness comeback. What I’m doing now is completely different than anything I’ve done previously; it’s been the most effective approach for gaining strength, for my lifestyle and natural affinity, and has resulted in the most obvious aesthetic changes in the shortest span of time.

What I Changed

The long and short is that I have incorporated max strength training and powerlifting in with my hypertrophy training. My initial goal was to get back into pre-pregnancy shape. But then I set my sights on getting strong. As I’ve mentioned, I avoided lower body work quite a bit both because of my hip dysfunction, but also because of my back condition (spondylolisthesis): Putting weight on my back is generally not a good idea when a vertebra is slipped forward permanently.

I knew nothing of my 1RM on any exercise and never even attempted to do anything that would tax me to failure below 6 reps. But I threw caution to the wind and started doing back squats and deadlifts in addition to my pull-ups, dips, overhead, and bench press. I worked in two days of max strength training a week (working in the 1-5 rep range) in addition to my higher rep work (6-12 rep range) the remaining days. I rarely go higher than 12 reps except for some lower body movements, like lunges and hip thrusts.

I didn’t run much except for maybe sprinting once a week. Yes, my back started to hurt more (that’s my issue which I’m currently addressing in physical therapy), but I got stronger, developed muscles in my legs that previously hit a sticking point, and noticed that my rectus abdominus (RA) was way more visible than ever before. (Bear in mind that my body fat percentage remains relatively stable with only minor fluctuations: Whether or not you “see” your six-pack has more to do with this than anything else.)

Still, I wasn’t doing abs aside from the deep core training work associated with repairing a Diastasis Recti, which for me, involved TVA activation, pelvic tilts, and quadruped stability work.

How to Develop Abs Without Spinal Flexion

The Journal of Strength and Conditioning reported in 2013 that integrated core work–those involving the distal trunk musculature such as the glutes and deltoids–recruited all the core muscles to a greater extent than any isolated movement.

This means functional activity that involves more of the body under a load will probably do a better job developing core strength than just focusing on the abs.

A more recent study wanted to compare functional movements to isolation movements with regard to hypertrophy of abdominal muscles. They found the targeted core movements were more effective in this regard compared to a lunge performed either in a stable, unstable, and with external resistance applied via resistance bands.

However, if you don’t thoughtfully critique these findings you might feel emboldened to say, “See!! Crunches and planks win!”

The problem here is that these lunges were not loaded heavily….they were either bodyweight or loaded with external trunk resistance by a band. In my opinion, this would need to be replicated with heavy loads—like the following study.

In 2018, the Journal of Human Kinetics compared a prone bridge (a plank) against a 6RM back squat and how much abdominal muscle contraction was generated by each. They found RA and external oblique (EO) activation was not significantly different between the two, yet erector spinae (ES) activation was higher with the squats.

In addition the RA activation increased as the set progressed during the back squat, while EO activation increased for the plank. Since the squat recruited ES and plank didn’t, they advocate for the heavy squat as the winner for core activation. The researchers concluded that the back squat was a better selection for athletes than isolation exercises to build core strength.

EMG tests measuring maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) of the ab muscles in question indicate that squats and deadlifts have a moderate activation effect on RA and EO muscles and are pretty comparable in that regard. However, the heavier you load a squat, the more EO activation you’ll see, and that’s across ALL squat positions.

A split squat or stationary lunge, will recruit more EO activity than a back squat. Also, deadlifts will result in greater muscle engagement on the ascending phase versus descending.

So, if you’re squatting and deadlifting with heavy enough weight to fail around 6 – 10 reps, you’re on the right track for some decent core development without doing crunches.

BUT, add in an overhead press, and those muscles will be working even harder than either squat or deadlift. (It would be unfair not mention here that a plank and Swiss ball jackknife also recruits RA and EO more than a squat or deadlift). If you’re interested in proper engagement of the TVA, focus on engaging while squatting; proper bracing will engage the core completely.

Using a weight belt or standing on an unstable surface? Appears to have no impact on muscle engagement of the core. Wowzas. Ditch the weight belt? (Well, I already have because it makes me pee my pants). What to do with that wobble board? Learn to balance I suppose!

Now if you really want to fire up your RA and EO, do some Strongman training. A study comparing deadlift and squat activation of these two muscle groups against non-traditional functional movements like a tire flip, shouldered keg walk, and Atlas stone lift, and found the latter group of movements activated the abs far more (think 50% activation compared to up to 85%). That’s major.

At the end of the day, most of us want to maximize our time in the gym, and certainly most of our clients do. Spending 15 minutes on abs at the end of an hour-long session once a week may be a waste of time if you can incorporate some heavier lifting, or even, some “fun”ctional movements like heavy tire flips. And for a more comprehensive review of the research check out this article on abdominal recruitment during functional exercise.

Have you been programming core work with your clients separately or are you a fan of integrating into a holistic workout?

References

https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/fulltext/2013/03000/Integration_Core_Exercises_Elicit_Greater_Muscle.5.aspx

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0212216

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6006542/

www.strengthandconditioningresearch.com/muscles/abdominals