Of the many buzz phrases circulating in the fitness world these days “deloading week” may be one that you may have heard many times, have contextually surmised its meaning, but may be uncertain of its necessity and appropriate application.

What is Deloading?

As it sounds, deloading week is a carefully timed week of active recovery within a periodized and progressively-loaded strength routine (or mesocycle) in which the client “deloads” by reducing either volume and/or intensity to allow for much-needed recovery.

Recently, scientists gathered a consensus on the definition of a deloading week: “Deloading is a period of reduced training stress designed to mitigate physiological and psychological fatigue, promote recovery, and enhance preparedness for subsequent training.”

But not everyone needs one.

Personally, I’m coming to the end of the first year-long macrocycle of strength and hypertrophy I’ve had in years, preceded by years of training with zero progression, and then post-partum-no-training-at-all. But recently I have been working harder than I ever have before and have been feeling the effects, both good and bad.

I began considering if I should program deloading into my own routine when I knew my family and I would be going away for a weekend. I’d miss two days in the gym anyway and my motivation has been waning as of late.

Also, a decades-long chronic back pain issue (stemming from a back condition and exacerbated by having babies) has been acting up lately and none of my usual tricks have been working to alleviate the discomfort. Add to that, a shoulder injury from lifting that has yet to make a full recovery.

I hadn’t much considered that the stress I’ve been putting on my body during my workouts might be the real root of these persistent pains.

Might it be time I deload for a week and allow my body some recuperation and recovery, or just pick up where I left off after my long weekend? And should I be doing this for my clients periodically as well?

Why Program a Deloading Week?

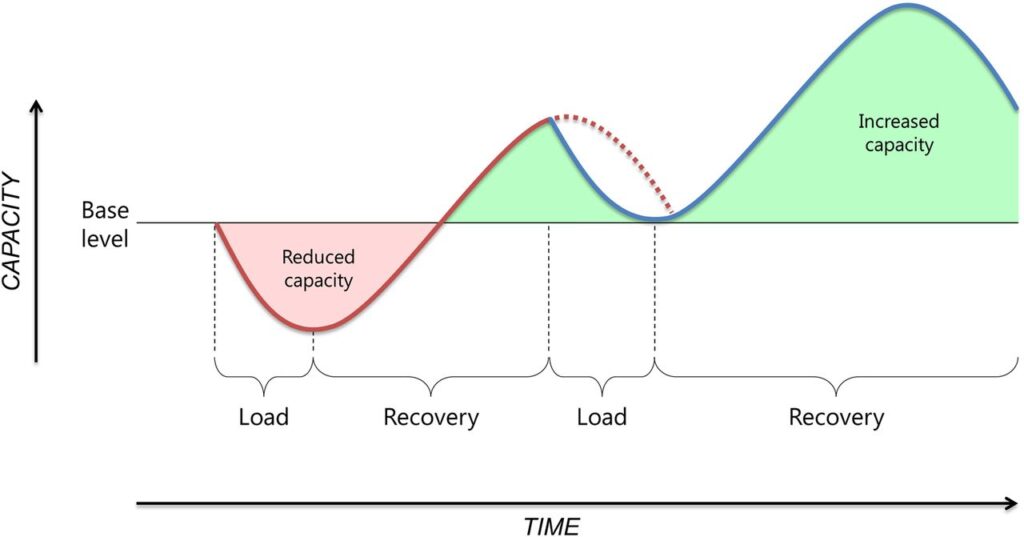

There is little scientific evidence specifically backing up a deloading week at present. In fact, recent research indicates that those who deload maintained similar muscle mass but lost some strength compared to those who didn’t deload. However, there is plenty of research pointing to an increase of musculoskeletal injury risk when overtraining is a factor. Furthermore, if an athlete does not allow for proper recovery within a progressively loading periodization program, prolonged fatigue and maladaptation, or abnormal training responses, are possible.

Given the amount of physiological stress placed on soft tissue and the psychological consequences of advanced weight training and highly-athletic sports, allowing a week or two of reduced demands seems to make good sense.

While programming a deloading week for someone who doesn’t truly require one won’t have deleterious effects, it simply is not worth doing.

To determine if your client truly needs a deloading week ask these questions:

- How old is he or she? Those of us who are 40 and over, whether or not we want to admit it, require more recovery time more frequently than our younger counterparts. That’s not to say 40+ year olds can’t be just as strong and hard-working, but as the body ages, so do the systems supporting it, running on depleted resources and slower processing times. If you’re elder clients workout regularly and intensely, a deloading week is a good insurance policy.

- How long has he or she been on a progressively loaded mesocycle? If you’ve been programming your client through increasingly intense, lower-volume training, then there comes a moment when a short active recovery period should be the next phase. However, if you’re client isn’t much for being pushed and likes to hang out in a comfortable, moderate-intensity zone (let’s face it, we all have a client like this), then there’s not much to deload from.

- Is he or she experiencing symptoms of overtraining? Our bodies are our best teachers. I’ve always been very good at listening to mine, but sometimes you have to know how to speak the body’s language. I thought my pain was more likely a result of tight muscles and poor prep work. Not overtraining. I may have been wrong.

When I look at the list of symptoms of overtraining, I can see a clearer connection.

Symptoms of Overtraining

- Lack of progress

- Negative attitude towards exercise

- Resting morning heart rate is 5 to 10 BPM too high

- Increase in body temperature

- A positive Keto-Stix reading (The use of Keto-Stix will indicate when too muscle is being cannibalized for energy

which can lead to metabolic acidosis, coma, and even death.) - Experiencing insomnia

- Development of chronic overuse injury (usually in the joints)

Certainly, when in doubt, err on the side of caution. Unexplained aches and pains can be a decent indication of requiring a recovery week or two. Adhering to a well-planned periodization program will not only progress your client towards a goal, but also factor in recovery time at proper intervals to prevent overtraining and overuse injuries to begin with.

What Does Deloading Week Look Like?

Coaches who have implemented deloading do not follow a cookie-cutter prescription. The idea is to decrease the training volume for about 5 to 7 days every 4 to 6 weeks. This will vary from client to client, of course. A drop in volume is generally the most favored approach. If your client is training five days a week and has been working a 3-day split, her leg routine might look like this:

Squats 95 lbs 4 x 12 (48 reps)

Leg Press 150lbs 3 x 12 (36 reps)

Hip Thrust 75lbs 3 x 15 (45 reps)

Deadlift 125lbs 3 x 12 (36 reps)

That equates to 165 total reps.

Deloading week you could decrease volume to 50% and keep the reps the same. Taking the above example you could cut the sets in half, or cut the reps in half. This is the easiest change to make with the least amount of calculation involved. So instead of 165 total reps, your client would perform about 82.

Alternatively, you could drop the intensity of the weight and keep the volume the same. Generally, about 50% of 1RM for each exercise would work. If your client is working in the 12-15 rep range, then they are lifting around 65% of their 1RM and can drop the weight a smidge.

Your client’s 75 lb hip thrust would decrease to 55 or 60 lbs for three sets of 15.

Whichever your approach, coach and prep your client through the process, making sure to thoroughly explain the reasoning of deloading week. Many people might feel like they are actually devolving or going backward by taking a less intense week of training. You may have to show them evidence of how deloading not only prevents injury and promotes recovery, but they will come back stronger than before when they resume normal training.

[sc name=”masterfitness” ][/sc]

References

- Kibler WB, Chandler TJ, Stracener ES. Musculoskeletal adaptations and injuries due to overtraining. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 1992;20:99–126.

- Mujika I, Hausswirth C, eds, Meeusen R. Overtraining syndrome. In: Mujika I, Hausswirth C, eds. Recovery for performance in sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2013:9–20.

- Bell, L, Nolan, D., Immonen, V., Helms, E., Dallamore, J., Wolf, M., Androulakis Korakakis, P., Front. Sports Act. Living, 21 December 2022 Sec. Elite Sports and Performance Enhancement

Volume 4 – 2022. Accessed: doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.1073223