Vertical push exercises command attention, both in the gym and beyond, for their ability to strengthen shoulders, fortify cores, increase confidence overhead, and instill a sense of power. In this article, we take a deep dive into this classification of human movement, the nuances, and the undeniable benefits of overhead pressing exercises.

Why Vertical Push?

Training the vertical push not only increases upper body strength and performance but also has a dramatic benefit to activities of daily living. As a fundamental movement, the vertical push is an important component of many training programs but requires adequate shoulder mobility and core bracing to perform a safe and effective repetition. Here are some important characteristics of the vertical push, also known as the overhead press:

- A fundamental movement pattern with movement in the shoulder and elbow joints in the overhead position (Kroell & Mike 2017)

- Relative to the spine, loading is in line, or parallel, with the spine

- As a multi-joint exercise, “it has the potential to use a high external load due to the cooperation of many muscle groups” (Błażkiewicz & Hadamus, 2022)

- Most variations are open-kinetic chain, however, some closed-chain variations exist

- There are endless unilateral and bilateral variations in the three planes of motion (Kroell and Mike 2017)

This article aims to help personal trainers understand the vertical push in order to help them make better programming decisions. This article will discuss the vertical push as a fundamental movement pattern, not a specific variation of the overhead press. It is not within the scope of this article to discuss shoulder mobility requirements, assessments, warm-ups, or corrective exercises.

This article will however empower personal trainers to supercharge their impact on clients’ fitness journeys by exploring key points widely applicable to various types of vertical pushes, regardless of the variation being performed. The following main points will be covered:

- Anatomy and Biomechanics

- Proper form

- Common Variations

- Cueing

- Modifications

Anatomy and Biomechanics

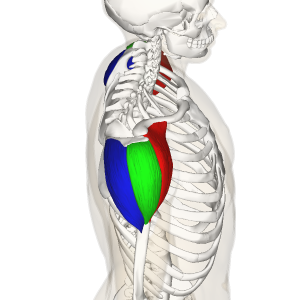

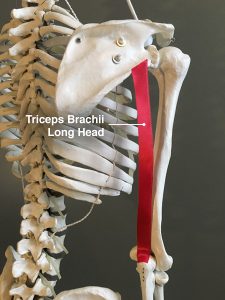

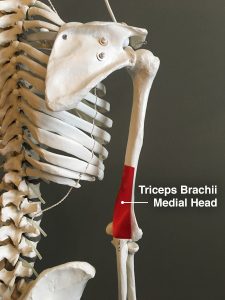

The muscles involved in vertical pushing movements consist of a large portion of the trunk and upper extremities, with contributions provided by the lower body during standing variations (Kroell & Mike, 2017). The anterior and medial deltoids along with the triceps brachii are the prime movers in the movement, while the scapula and trunk muscles provide proximal stability.

The first phase of the vertical push involves flexion and internal rotation of the shoulder joint. concentric work of the clavicular head of the pectoralis major, coracobrachialis, and anterior deltoid muscles. The degree of internal rotation is concentrically initiated by the infraspinatus and teres minor muscles (Escamilla et al, 2009).

Extension of the elbow joint is resultant of the concentric contraction of the triceps muscle and the ulnar muscle, the latter of which is an active stabilizer of the elbow joint. When flexion exceeds 60°, the serratus anterior, lower, and upper trapezius muscles move the scapula externally by creating a “co-activation” (Escamilla et al, 2009).

The shoulder girdle is active from about 80–90° of shoulder flexion, including up to 30° of rotation in clavicle joints. After exceeding 90° flexion, trapezius, pectoralis minor, and rhomboid muscles are activated to provide necessary stabilization of the scapula (Anderson et al, 2012).

Shoulder abduction and stabilization during the articulation at the glenohumeral joint is brought about by (Anderson et al, 2012; Kroell & Mike, 2017):

- Supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis (rotator cuff)

- Serratus anterior

- Lower, middle, and upper trapezius

- Levator scapulae

- Rhomboids

The thoracic spine experiences both flexion and extension throughout the range of motion of a vertical push(Kroell & Mike, 2017). Since the spine is loaded directly through vertical pushing, spinal stability is crucial. This requires bracing the trunk to generate sufficient intra-abdominal pressure, including (Kroell & Mike, 2017):

- Transverse abdominis

- Rectus abdominis

- External and internal oblique

- Diaphragm

- Spinal erectors

Proper Form for a Vertical Push

With the variety of vertical push exercises, it is not within the scope of this article to discuss the nuanced differences in form across different vertical pushing variations. Therefore, a bird’s eye view will be taken that can be generally applied.

Pre-Ascent

Before the ascent, the trunk should be stabilized with a co-contraction of the glutes and abdominals to ensure the hips do not have excessive anterior pelvic tilt (Kroell & Mike, 2017). In many exercises, trunk stabilization is often achieved through overcompensation of the spinal erectors which places the lumbar spine in excessive lordosis (Ulm 2023).

Next, the elbows should be pointed somewhere between the frontal plane and the sagittal plane. The scapular plane, or around 30 degrees of abduction, is encouraged by literature because it has been shown to increase the stability of the humeral head in the glenoid fossa by increasing the activity of the rotator cuff muscles (Reinold et al, 2009.

Keep the scapulae depressed and retracted to ensure they have proximal stability for the muscles to create distal forces. One common error is to begin with the hands positioned too far down which internally rotates and anteriorly tilts the shoulder, causing a loss in stability.

Lastly, position the wrist over the elbow for maximum stability. Ensure that the wrists do not move medially towards one another in the frontal plane.

In summary, here is the setup before ascending the load:

- Stabilize hips and spine

- Point elbows slightly forward and down towards the ground, but not straight down

- Stabilize scapulae

- Maintain wrists over the elbows, without moving laterally or medially in the frontal plane

Ascent and Descent

The movement is initiated by the prime movers. Push the load vertically while maintaining stability in the scapulae, glenohumeral joints, and spine. Ensure full elbow extension and shoulder flexion at the end of the ascent, and then lower the load back to the starting position.

The path of the load or hand holding the load should be relatively straight up. During the last part of the ascent, ensure that there is no excessive thoracic extension (rib flair) or no excessive lumbar lordosis (low back arching). The more stable the spine is, the more stable the platform is to produce overhead force (McKean & Burkett, 2015).

In summary, here are the steps for the ascent and descent:

- Push the load straight up while maintaining stability in the hips, spine, and shoulders

- Achieve full elbow extension and shoulder flexion at the top of the movement

- Avoid any unwanted movement, such as excessive thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis.

Common Variations

Vertical push exercise variations can be done with relatively the same technique (Waller et al, 2009). The differences arise from the variations being unilateral instead of bilateral, or the hands being connected by the load, which changes the mobility and stability demands of the shoulder (Waller et al, 2009).

One study in 2022 concluded that different variations provide different stimuli to the muscles and may be used accordingly during the training routine (Coratella et al, 2022). Note, that different techniques can affect the sequence of muscle activation and the magnitude of stress forces in ligaments and tendons (Błażkiewicz & Hadamus, 2022).

Barbell Overhead Press

- Heaviest loading potential of all free-weight variations due to the stability provided by the nature of the bar (Błażkiewicz & Hadamus, 2022)

- The most technical of the non-power-based vertical pushing variations, but the least technical variation compared to the snatch, push press, or jerk (Kroell & Mike, 2017)

- A study in 2010 compared EMG activity between barbell overhead press and dumbbell overhead press and reported similar EMG activity in the anterior and medial deltoid despite that the dumbbell load was only ∼86% of the barbell load (Kohler et al, 2010)

Dumbbell Overhead Press

- Multiple hand positions, such as a pronated grip or a neutral grip

- A greater degree of freedom of abduction in the glenohumeral joint

- Bilateral and unilateral variations

- A study in 2020 compared EMG activity between standing and sitting overhead pressing (dumbbells and barbells) and found that standing elicited higher EMG activity despite less load compared to sitting (Saeterbakken & Fimland, 2013)

Kettlebell Overhead Press (bottom-up included)

- When pressing a kettlebell, its center of mass is behind the elbow joint rather than in line

- A 2022 study found that the kettlebell overhead press resulted in slightly higher muscle activation than the dumbbell counterpart (Błażkiewicz & Hadamus, 2022)

- In the bottom-up position, there is a greater stimulus to actively control the load from flopping over to the side

- In the bottom-up position, the intense gripping increases rotator cuff recruitment while also improving grip strength

Landmine Shoulder Press

- Less overhead mobility required

- Great at cueing stability

- It resembles more closely to an incline press since the movement isn’t pure overhead

- Immense customization with stance, attachments, and more

- Often used with clients with shoulder considerations

Machines or Plate-Loaded Devices

- Compared to free-weight standing exercises, “sitting in a chair will spread the forces into the back pad and seat, thus adding support to help stabilize the body” (Waller et al, 2009)

- “The added stabilizing effect of the seat may allow a person to press slightly greater loads because of the reduction in recruitment of other muscles (leg muscles) needed for stabilization in an overhead press” (Waller et al, 2009)

Cueing

Shoulders

During most exercises, we want proximal stability during distal mobility. This means that while the weight is being moved vertically by the arms, there should be stability at the attachment point of the arms, such as the scapulae and glenohumeral joint. One common problem during the vertical push is failure to stabilize unwanted movement in the scapulae.

This often occurs as the upper traps shrug or the shoulders internally rotate or roll forward. Another issue is the elbows flaring laterally, as a result of shoulder instability. Shoulder instability can also result from too narrow of a grip or the forearms internally rotating medially. A lack of control in the posterior and external rotator muscles of the shoulders can cause this. Try these cues to coach your clients’ shoulders:

- “Shoulders down and back”

- “Maintain a long neck- don’t let the shoulders elevate”

- “Elbows pointed forward as if they were lasers shining on an object”

- “Wrists over elbows”

Spine and Core

Everything in the body is connected to the spine. A potential issue in the spine or core area in the vertical push is core instability. Excessive arching in the back (hyperlodosis) or rounding of the back (hyperkyphosis) are the most common issues. If these are not chronic issues, but instead are due to a lack of connecting with the proper musculature, cueing the glutes and abdominals will be instrumental in reducing these issues.

- “Keep your spine as still as possible during the exercise”

- “Lower your rib cage by contracting your abs”

- “Make your core a cylinder like this foam roller”

If these cues fail to correct the movement patterns, corrective work at the shoulder and core may be necessary.

Modifications

Sometimes making training modifications can lead to a dilemma: does this modification continue to reinforce a deficiency? Can the deficiency be addressed during another part of the workout so the training can continue? Does this modification’s benefits outweigh its cons? These are all important decisions to consider when making a modification in your clients’ training program, including in their vertical push exercises.

The goal of the modification is to remove a barrier holding the client back. Modifications can be used to either provide more of a challenge or simplify the exercise to allow for better form. Below are some modifications that can help with common needs that come up when training the vertical push.

Shoulder Instability during Vertical Push

If your client is having difficulty with instability in the core or shoulders, you can make their base of support more stable by changing their stance or supporting their core. Aim for the next most “functional” position when choosing a modified stance. If instability still presents, try the next most stable option.

Standing Position or Stance

- Split stance or single kneeling

- Sit on a bench with the feet pushing into the floor

- Bring the client down to the floor to sit or have them sit on a couple of mats or pads

- Sit on a chair

Modality

- Alternating reps, such as one arm lift at a time

- Unilateral vertical pushes

- Machine vertical pushes

Difficulty with Overhead Mobility

- Landmine press

- Incline bench set at less than 90 degrees

Increase Core Challenge

- Sit flat on the floor in different positions, such as hips at 90-90 or legs abducted, knees extended, and toes dorsiflexed

- Heavy unilateral pushes

- Use less stable loads such as sandbags, hanging weights from bands, or using an unstable bar

Conclusion

In conclusion, vertical pushing exercises are essential components of any well-rounded fitness program, and they should hold a special place in every personal trainer’s toolbox. These movements not only help develop strong and sculpted shoulders but also contribute to overall upper body strength and stability.

From the classic standing barbell press to variations like dumbbell presses, seated presses, and even handstand push-ups, there a myriad of options to cater to various fitness levels and goals.

As personal trainers, we must educate our clients about the significance of vertical pushing exercises, ensuring they perform them with optimal form and technique to maximize their benefits and minimize the risk of injury. These movements not only enhance aesthetic appeal but also improve functional fitness, making everyday activities easier and injury-free.

So, let’s continue to inspire and educate our clients, helping them build stronger, healthier, and more resilient bodies through the power of vertical pushing. Together, we can elevate their fitness experience and lead them toward a happier, more active life.

Learn more in our Functional Training Specialist as a part of our Continuing Education Course Series.

References

- Andersen, Christoffer H.1,2; Zebis, Mette K.2; Saervoll, Charlotte1; Sundstrup, Emil1; Jakobsen, Markus D.1; Sjøgaard, Gisela2; Andersen, Lars L.1. Scapular Muscle Activity from Selected Strengthening Exercises Performed at Low and High Intensities. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 26(9):p 2408-2416, September 2012. | DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823f8d24

- Błażkiewicz M, Hadamus A. The Effect of the Weight and Type of Equipment on Shoulder and Back Muscle Activity in Surface Electromyography during the Overhead Press-Preliminary Report. Sensors (Basel). 2022 Dec 13;22(24):9762. doi: 10.3390/s22249762. PMID: 36560129; PMCID: PMC9781216.

- Coratella G, Tornatore G, Longo S, Esposito F, Cè E. Front vs Back and Barbell vs Machine Overhead Press: An Electromyographic Analysis and Implications For Resistance Training. Front Physiol. 2022 Jul 22;13:825880. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.825880. PMID: 35936912; PMCID: PMC9354811.

- Dicus JR, Holmstrup ME, Shuler KT, Rice TT, Raybuck SD, Siddons CA. Stability of Resistance Training Implement alters EMG Activity during the Overhead Press. Int J Exerc Sci. 2018 Jun 1;11(1):708-716. PMID: 29997723; PMCID: PMC6033506.

- Escamilla RF, Yamashiro K, Paulos L, Andrews JR. Shoulder muscle activity and function in common shoulder rehabilitation exercises. Sports Med. 2009;39(8):663-85. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200939080-00004. PMID: 19769415.

- Ghigiarelli, Jamie J. PhD, CSCS1; Berrios, Xavier M.2; Prendergast, James M. MS, CSCS1; Gonzalez, Adam M. PhD, CSCS1. The Viking Press. Strength and Conditioning Journal 43(5):p 123-126, October 2021. | DOI: 10.1519/SSC.0000000000000604

- Dicus JR, Holmstrup ME, Shuler KT, Rice TT, Raybuck SD, Siddons CA. Stability of

Resistance Training Implement alters EMG Activity during the Overhead Press. Int J

Exerc Sci. 2018 Jun 1;11(1):708-716. PMID: 29997723; PMCID: PMC6033506. - Escamilla RF, Yamashiro K, Paulos L, Andrews JR. Shoulder muscle activity and

function in common shoulder rehabilitation exercises. Sports Med. 2009;39(8):663-85.

doi: 10.2165/00007256-200939080-00004. PMID: 19769415. - Ghigiarelli, Jamie J. PhD, CSCS1; Berrios, Xavier M.2; Prendergast, James M. MS,

CSCS1; Gonzalez, Adam M. PhD, CSCS1. The Viking Press. Strength and Conditioning

Journal 43(5):p 123-126, October 2021. | DOI: 10.1519/SSC.0000000000000604 - Kroell, Jordan BS, CSCS, USAW1; Mike, Jonathan PhD, CSCS*D, NSCA-CPT*D,

USAW2. Exploring the Standing Barbell Overhead Press. Strength and Conditioning

Journal 39(6):p 70-75, December 2017. | DOI: 10.1519/SSC.0000000000000324 - Mather RC 3rd, Koenig L, Acevedo D, Dall TM, Gallo P, Romeo A, Tongue J, Williams G

Jr. The societal and economic value of rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013

Nov 20;95(22):1993-2000. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01495. PMID: 24257656; PMCID:

PMC3821158. - McKean, M. R., & Burkett, B. J. (2015). Overhead shoulder press–In-front of the head or

behind the head?. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 4(3), 250-257. - Kohler JM, Flanagan SP, Whiting WC. Muscle activation patterns while lifting stable and unstable loads on stable and unstable surfaces. J Strength Cond Res. 2010 Feb;24(2):313-21. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c8655a. PMID: 20072068.

- Kroell, Jordan BS, CSCS, USAW1; Mike, Jonathan PhD, CSCS*D, NSCA-CPT*D, USAW2. Exploring the Standing Barbell Overhead Press. Strength and Conditioning Journal 39(6):p 70-75, December 2017. | DOI: 10.1519/SSC.0000000000000324

- Mather RC 3rd, Koenig L, Acevedo D, Dall TM, Gallo P, Romeo A, Tongue J, Williams G Jr. The societal and economic value of rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013 Nov 20;95(22):1993-2000. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01495. PMID: 24257656; PMCID: PMC3821158.

- McKean, M. R., & Burkett, B. J. (2015). Overhead shoulder press–In-front of the head or behind the head?. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 4(3), 250-257.

- Reinold MM, Escamilla RF, Wilk KE. Current concepts in the scientific and clinical rationale behind exercises for glenohumeral and scapulothoracic musculature. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009 Feb;39(2):105-17. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2009.2835. PMID: 19194023.

- Saeterbakken AH, Fimland MS. Effects of body position and loading modality on muscle activity and strength in shoulder presses. J Strength Cond Res. 2013 Jul;27(7):1824-31. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318276b873. PMID: 23096062.

- Ulm, R. (2023). Strength Training Effectively without Lower Back Pain. NSCA National Conference 2023. Las Vegas; Nevada, USA.

- Waller, Mike MA, CSCS*D, NSCA-CPT*D; Piper, Tim MS, CSCS*D; Miller, Jason MS, CSCS. Overhead Pressing Power/Strength Movements. Strength and Conditioning Journal 31(5):p 39-49, October 2009. | DOI: 10.1519/SSC.0b013e3181b95a49

- Zhou S, Chen S, Liu X, Zhang Y, Zhao M, Li W. Physical Activity Improves Cognition and Activities of Daily Living in Adults with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan 22;19(3):1216. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031216. PMID: 35162238; PMCID: PMC8834999.